On Burn’s Night (25 January) I introduced William Richmond who, at the age of 20, enlisted in the 10th (Service) Battalion of the Royal Highland Regiment (Black Watch) on 11 September 1914. After finding themselves in various English camps during 1915 and spending two months in France the Battalion, with the rest of 26th Division, started heading off for Salonika – via Marseille – in November 1915.

Continue reading “William Richmond and 10/Black Watch (2)”Category: Faces of Salonika

A series of images of those – from all sides – who took part in, or witnessed, the First World War campaign in Macedonia from 1915 to 1918.

A lost world …

Although the White Tower would have been familiar, my late grandfather would not have recognised modern Thessaloniki – the vibrant Greek city rebuilt after the great fire of 1917 and developed in the decades after that. To him and other members of the British Salonika Force who passed through it was very much an eastern city – not always remembered fondly – populated by a multiplicity of different peoples. Notable among the inhabitants was the strong Jewish community, but the fire of 1917, subsequent upheavals and the appalling events of the Holocaust changed the city forever.

Continue reading “A lost world …”William Richmond and 10/Black Watch (1)

Happy Burn’s Night to all our Scottish readers – wherever you are in the world – and all those Sassenachs who, like me, enjoy nothing more than tucking into a haggis with ‘neeps and tatties’, washed down with a ‘wee dram’!

This seems an ideal occasion to celebrate one of the Scottish units of the British Salonika Force – 10th (Service) Battalion, Royal Highlanders (Black Watch). Formed in Perth in 1914 the Battalion joined 26th Division (77th Brigade) and soon found itself far from the Highlands: on Salisbury Plain, in Bristol and Sutton Veny in Wiltshire. In September 1915 it sailed for France but, after just two months, it was off to Salonika where it remained until returning to the Western Front in June 1918.

Continue reading “William Richmond and 10/Black Watch (1)”Dr Isobel Tate

‘X’ (formerly Twitter) is not a favourite medium of mine but it can, in some circumstances, be an informative and interesting forum. In the past year the Society has set up an account and we have managed to both share and learn from this online community. For example, in a series of posts, @DanielJPhelan (Speaker, tour guide, & EOHO volunteer for @CWGC ) shared a thread about a discovery while on holiday in Malta. During his stay, Dan visited Pieta Military Cemetery and it was there that he found the grave of Dr Isobel Tate.

On his return home, Dan researched and shared his findings in a series of posts and images on X (Twitter). Thanks Dan for sharing your research!

“Isobel Addey Tate was born, around 1874, in Country Armagh, Northern Ireland. At a time when female doctors were rare, she studied medicine at Queens University, Belfast graduating in 1899. Continuing her studies, she qualified as a Doctor of Medicine in 1902.

After qualifying, a huge achievement, she moved to England and held a number of positions in hospitals and medical institutions. However, it seems pursuing her career in medicine was not easy…

In 1904, while working at the Burnley Workhouse, Dr Tate obtained a Diploma in Public Health from Victoria University, Manchester. It was thought at the time that Dr Tate was the only lady in the kingdom who had ever secured that honour.

In 1915, with the Great War being fought, Dr Tate volunteered to serve with the Serbian Relief Fund. The relief fund was set up and commanded by Mrs Mabel St Clair Stobart. It had seven women surgeons and doctors, which included Dr Tate.

While serving with the Serbian Relief Fund, Dr Tate contracted typhoid and returned home to convalesce. Once well again she became a radiographer at Graylingwell War Hospital, near Chichester. Feeling she ‘was not doing enough’ Dr Tate offered to go abroad again.

Isobel Tate volunteered for service with RAMC and embarked for Malta in August 1916. In Malta she treated sick and wounded servicemen, including casualties from Gallipoli and Salonika. While working at Valletta Military Hospital she became ill. Sadly, on 28th January 1917, Dr Isobel Tate succumb to her illness and died of typhoid fever.

The funeral of Dr Isobel Tate took place on Tuesday 30th January 1917. Her flag-draped coffin was carried by medical officers, flanked by two lines of wreath carrying NCOs from the RAMC. The firing party contained 40 men of the Royal Garrison Artillery. A lengthy train of medical officers, officers from other units, and local members of the medical profession followed her coffin. At the graveside assembled ‘lady doctors’, principal matron, matrons, sisters, and nurses, from all hospitals and camps on the island.

It’s incredible to think that Isobel Addey Tate lived, served, and achieved so much, in an era before women even had the vote. I think this quote from a newspaper at the time is very fitting.”

You can read the complete thread from Dan on Twitter @DanielJPhelan:

The nature of ‘social media’ does not really allow for detail and detailed discussion, so Dan’s account of Isobel Tate’s life is necessarily short. If you would like to read more about her life, and the challenges she and other women faced, there is a more in-depth examination here.

Advanced Dressing Station on the Struma 1916 (Henry Lamb)

I’m grateful to a recent correspondent with the Society for bringing to attention (to me at least!) the work of artist Henry Lamb. In 2014, the Whitworth Art Gallery in Manchester had an exhibition, The Sensory War, to mark the 100th anniversary of WW1. One of the works exhibited was by Lamb: Advanced Dressing Station on the Struma 1916

Ana Carden-Coyne, who co-curated the exhbition Visions of the Front 1916-18, for the Somme centenary also featured the painting and describes it in this way:

“The scene of a dressing station focuses on the relationship between a wounded man and a stretcher-bearer, who attends him with a cup of water, a great relief that many soldiers wrote about as the comfort given between men. Thirst and cold were understood much later in the war as signs of hemorrhage and shock. The bearer’s hand gently touches the wounded man’s head, providing comfort symbolic of the pietà (Christian iconography of Mary cradling Jesus’ corpse). Indeed, the pietà was often used in war-time humanitarian images of nurses caring for wounded men. But Lamb transforms the theme into an effigy of masculine care and the intimate brotherhood of shared suffering. Placed on the ledge of a shallow trench, the stretcher resembles an altar. In the right hand corner is a Thomas splint used for compound fractures, from which soldiers could die. Pathos is also created by the figure on the left, head in hand, perhaps affected by malaria, a common disease of this front, or perhaps a reference to psychological suffering. The central figure stands over the patient, staring pensively into the distance. Made three years after the end of the war, the composition of this painting symbolises the pain and succour of the entire conflict.”

There’s also discussion of the painting by one of the team at The Whitworth here:

Henry Lamb was born in Australia in 1883 and educated at Manchester Grammar School, before studying medicine at Manchester University Medical School and Guy’s Hospital in London. He abandoned medicine in 1906 to study painting at the Chelsea School of Art but “with the outbreak of the first world war Lamb returned to his study of medicine and served as a doctor in the Royal Army Medical Corps in France, Salonika and Palestine where he was awarded the Military Cross. He was not an official war artist but was always sketching and drawing in spare moments. These sketches with memories from his time on the Macedonian Front and the Palestine campaign formed the basis of large-scale paintings made after the war. ‘Irish Troops in the Judaen Hills’, now in the Imeperial War Museum, and ‘Advanced Dressing Station on the Struma’ for Manchester City Art Gallery are amongst the most extraordinary of his career. In 1928 he married Lady Pansy Pakenham and moved to the quiet Wiltshire village of Coombe Bissett where they would remain for the rest of their lives. Lamb was appointed an official war artist for the second world war and after first wanting to document the war cabinet decided on portraits of soldiers and studies of servicemen at work across the South of England. At the same time as his appointment as a war artist Lamb was elected as an associate of the Royal Academy and a Trustee of both the National Portrait Gallery and the Tate. He was finally awarded full membership of the Royal Academy in 1949.” Sources here and here.

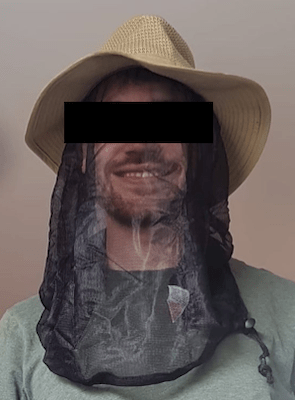

Mind the mozzies!

With family members heading off to tropical climes, I was quick to share my ‘specialist knowledge’ of anti-mosquito precautions – based entirely on reading about the BSF – and shared this splendid photo with the travellers:

Lance Corporal Harrison, 12th Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers, wearing protective anti-mosquito clothing as issued to troops on night duty during the summer months. Photograph taken at Bowls Barrow, 2 June 1918. © IWM HU 82035

I’m not sure how impressed they were, but I thought it gave an excellent impression of the precautions to take. So I was especially pleased to see anti-mosquito face veils at a reasonable price in a well-known hiking and outdoors shop and promptly bought one for each member of the party. I have seen them in use, although this was in the UK and – I suspect – more to humour me than a serious indication of an intention to wear them in foreign parts.

Just think how chuffed members of the BSF would have been to have these – they even look great with a slouch hat …

(of course, in proper use the veil should be tucked in at the neck!)

Well, they are on their travels and I don’t like to ask if they’ve used them yet, but I will be looking out for traces of mosquito bites on their faces when they return!

If you are travelling this summer, I hope you manage to avoid mosquitoes and midges. If not, maybe you should invest in one of these veils as a practical tribute to the BSF!

The Illustrated War News

That infallible organ of facts and certainty, Wikipedia, has this to say about the ‘Illustrated War News’, At the outbreak of the war, the magazine ‘The Illustrated London News’ began to publish illustrated reports related entirely to the war and entitled it ‘The Illustrated War News’. The magazine comprised 48 pages of articles, photographs, diagrams and maps printed in landscape format. From 1916 it was issued as a 40-page publication in portrait format. It was reputed to have the largest number of artist-correspondents reporting on the progress of the war. It ceased publication in 1918. Source

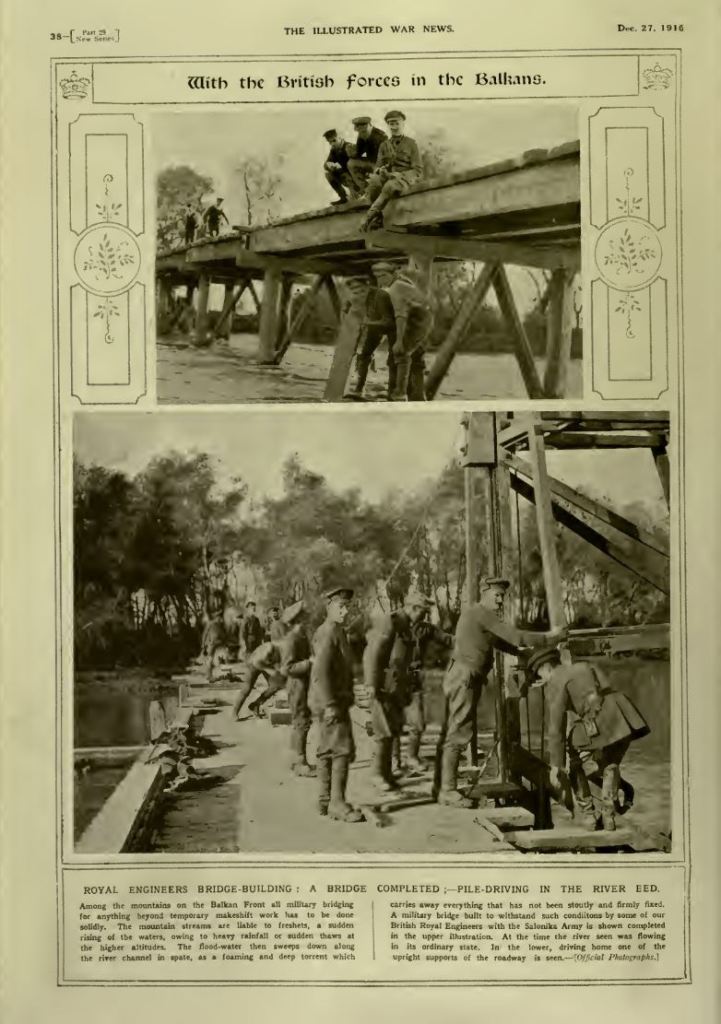

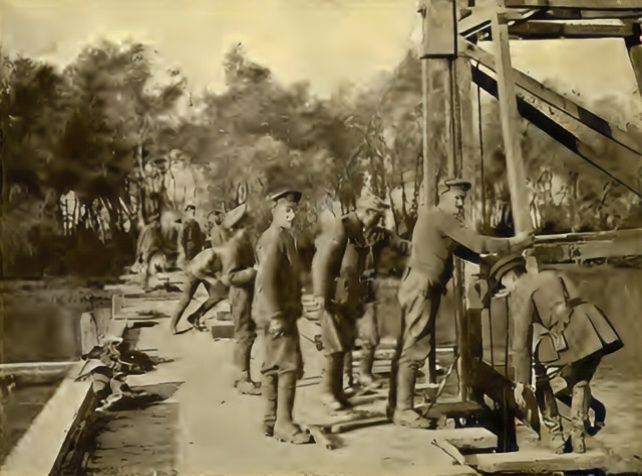

There are digitised copies of ‘The Illustrated War News’ on our SCS Digital Collection DVDs. I thought it might make an interesting occasional series to draw on the magazine and take a look at how the Salonika Campaign was reported. This report from December 27, 1916, for example, shows the Royal Engineers at work, “Among the mountains on the Balkan Front…”

The text reads: Among the mountains on the Balkan Front all military bridging for anything beyond temporary makeshift work has to be done solidly. The mountain streams are liable to freshets, a sudden rising of the water, owing to heavy rainfall or sudden thaws at the higher altitudes. The flood-water then sweeps down along the river channel in spate, as a foaming and deep torrent which carries away everything that has not been stoutly and firmly fixed. A military bridge built to withstand such conditions by some of our British Royal Engineers with the Salonika Army is shown completed in the upper illustration. At the time, the river seen was flowing in its ordinary state. In the lower, driving home one of the upright supports of the roadway is seen.

The Illustrated War News December 27, 1916.

Celebrating a Salonika VC Winner

The Victoria Cross was first introduced on 29th January 1856 to honour acts of valour during the Crimean War. Two VCs were awarded in the Macedonian campaign, one in 1916 and one in 1918. It’s the first of these, to Private Hubert William Lewis of 11/Welsh, that I want to celebrate today.

Continue reading “Celebrating a Salonika VC Winner”Happy New Year!

We wish all our members, friends, their families and loved ones all the very best for a happy and healthy 2023. And we send special Hogmanay greetings to our Scottish members and friends.

Continue reading “Happy New Year!”It’s Panto time again … Oh! yes it is!

This year I have been to a pantomime for the first time in about 25 years. We bought tickets last year but Covid meant that we didn’t get to use them. This year’s offering was Robin Hood and the Babes in the Wood by the Littleport Players. Not one of the more common productions – and not one I’ve come across in Salonika – but I do recall going to see it with my grandfather when I was a nipper. For many years he and I went to East Barnet Royal British Legion Hall to see the show put on by – I think – the Warren Players and Concert Party. You don’t hear of concert parties these days, so that makes me feel very old.

Continue reading “It’s Panto time again … Oh! yes it is!”