I doubt that members of the Salonika Campaign Society really need International Women’s Day to remember the service and sacrifice of the women of the Scottish Women’s Hospital who served in the Balkans. The Society has remembered them in books, in talks and presentations, at events and in articles, both printed and online. Even so, it may be helpful to have a reminder of these redoubtable women and their noble enterprise, through the graves of just four of their number. I photographed these on a visit to Thessaloniki ten years ago, at the CWGC Lembet Road Military Cemetery. They are: Sister Mary de Burgh Burt, Sister Florence Missouri Caton, Masseuse Olive Smith and Alice Annie Grey.

Continue reading “Remembering …”Category: Hospitals

Mettle and Steel: the AANS in Salonika

Searching for information recently about nursing in Salonika, I stumbled across Mettle and Steel: the AANS in Salonika. It’s an account of the punishing nature of Australian military nursing in Salonika. From 1917, Australian nurses were sent into this difficult and unfamiliar theatre of war to relieve the British, French and Canadian nurses and to provide nursing care to British soldiers and prisoners of war. As nursing ‘our boys’ was a major motivation for overseas service, it was something of a disappointment for many that they could not nurse Australian soldiers.

A group of Australian Army nurses about to depart from Adelaide for Salonica, 14 June 1917. From the left: Miss Molly Wilson, Mrs J. Tyers, Miss Edith Horton, Miss Marion Geddes, Miss Laura Begley, Mrs Jessie McHardie White (Principal Matron), Mrs Forsyth (wife of General Forsyth), Miss Violet Mills (Matron of No 5 Australian General Hospital who was on a visit to Adelaide), Miss Alice Prichard and Miss Florence G. Gregson.

I hadn’t quite appreciated the scale and complexity of the Australian nursing presence: four contingents were dispatched via Egypt, under constant U-boat threat, and then distributed across a shifting network of British hospitals in Greece and the surrounding hills. Each unit was allocated one Matron, ten AANS Sisters and eighty Staff Nurses. The nurses were led by senior matrons such as Jessie McHardie White, who oversaw not only clinical standards but the welfare and morale of hundreds of nurses. Staff Nurse Lucy May’s personal account helps convey the experience of Salonika in winter:

[12 October 1917] Water racing thru wards & reached halfway up bedsteads, haversacks, boots, socks, pants floating down road…

[21 October] Lanterns blowing out & leaving you in dark…

[23 October] Still don weather attire, only wearing men’s pyjama pants, putties, gum boots, man’s shirt also. Had dress tucked around waist all night…

[2 November] Imagine me [on night duty] over my ankles in mud, dragging one foot out then other foot & standing on one leg in grim peril or sitting down hastily…feeling the rain oozing through my mack. This is the life?”

As winter ended, the nurses then faced oppressive summers dominated by malaria. The AANS uniform was adapted in an attempt to counter the mosquito risk. A ‘mosquito proof’ nurse would be clad in her working dress, huge gloves, rubber boots and thick veil which, according to Lucy Tydvil Armstrong:

“made it quite impossible to carry out our duties, when men were rigoring and vomiting all night long, we just had to do away with the precautions, & run the risk of being bitten with mosquitos.”

A group of Australian Army Nursing Service nurses at the 52nd British General Hospital at Kalamaria, Greece ready for night duty wearing headdress provided for protection against mosquitoes. C 1918.

Despite the precautions, Matron McHardie White later reported that, ‘most of the nurses were affected by it [malaria] one time or another…’ By August 1918 45 nurses had been sent back to Australia from Salonika and another 14 were waiting to go, mostly on grounds of ill health. The death of Sister Gertrude Evelyn Munro in 1918 underlines the very real cost of the AANS service.

Sisters Gertrude Evelyn Munro and Amy Christie of the AANS. The photograph was probably taken at the 60th British General Hospital, Salonica.

Despite deteriorating health and official doubts about the value of their continued presence, the nurses remained in Salonika until after the war ended, not returning home until early in 1919. Their courage and professionalism were acknowledged through praise and decorations from British, Serbian and Greek authorities. Matron McHardie White, as just one example, was awarded the Serbian decoration of the Order of St Sava and was made a Member of the British Empire.

Nurses’ Narratives

It’s always interesting to read first-hand accounts of experience and so it was good to see that some diary and retrospective narratives written by the AANS nurses have been, and are being, transcribed. Staff Nurse Vivian A Lee Shea, for example, recalled,

We arrived in the midst of summer & the height of the Malaria & Dysentry season, & work commenced right away. We had much to learn. We were all new to each others ways & the medical Staff & personnel had only just landed as we ourselves had.

The Hospital was rather well situated at an elevation of about 2000 ft above sea level & this gave us a cooler summer, but made it impossible to live there in the winter months. During the winter months we occupied the Prisoners of War Hospital in the Base area. Here we nursed British Troops, as well as prisoners of War, the latter were representatives from practically every one of the Baltic States. Germans Bulgars, Turks, Romanians, Greeks Albanians & Serbs, in fact any one found in enemy lines.

Annie E Major-West remembered,

We remained in Salonika till February 1919, during the whole time the work was very heavy at times the hours on duty were particularly long. these conditions were occasioned by the prevalence of Sickness amongst the Sisters and Medical Officers.

Frequently the Bulgars & Germans were over in Planes endeavouring to bomb

the Town but the Vicinity of the Hospital was never damaged, during the Month

of August 1917 the town was partially destroyed by fire, Supposed to have

been the work of Spies.

- Read the full article Mettle and Steel: the AANS in Salonika.

- Search for first hand accounts here: https://transcribe.awm.gov.au/transcription

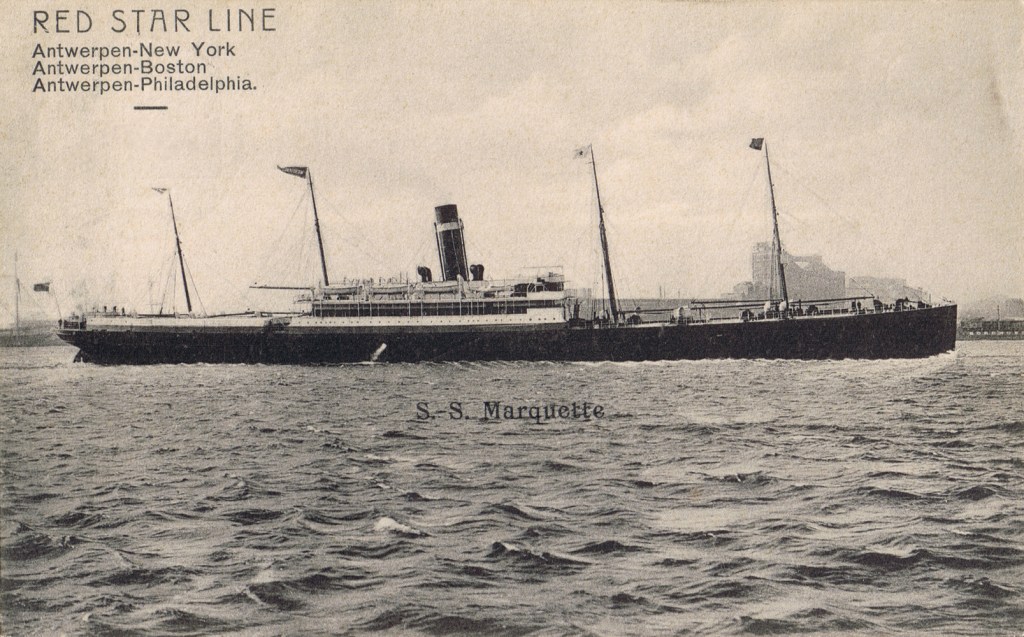

The Sinking of the Marquette, 1915

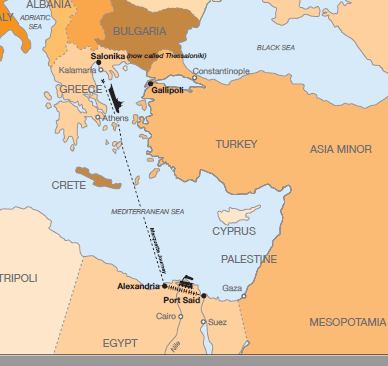

A little over 110 years ago, on Saturday 23 October 1915, the British transport ship Marquette was torpedoed by the German submarine U-35 as it entered the Gulf of Salonika. The ship sank within ten minutes. Of the 741 people on board, 167 died, including 32 New Zealanders – ten of whom were nurses.

The New Zealand Nurses

Most of the New Zealanders aboard were members of the 1st New Zealand Stationary Hospital. They had been serving in Egypt, treating casualties from Gallipoli, and were being transferred to support Allied operations in the Balkans. Among them was Staff Nurse Margaret Rogers, who had enlisted only months earlier in July. Indeed, The New Zealand Army Nursing Service was itself new and only established early in 1915.

Image source: Nurse Margaret Rogers, URL: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/photo/nurse-margaret-rogers, (Manatū Taonga — Ministry for Culture and Heritage), updated 28-May-2024

The Marquette, originally a cargo vessel, had been adapted for wartime transport.

Image source: https://ww100.govt.nz/no-ordinary-transport-the-sinking-of-the-marquette

When it departed from Alexandria on 19 October, it carried medical personnel, British troops, over 500 mules, and ammunition. Although accompanied by a French destroyer during part of the journey, the escort departed the day before the attack.

At approximately 9:15 a.m., witnesses reported sighting a torpedo shortly before it struck the starboard side of the ship. The impact caused the vessel to list sharply. Despite the suddenness of the event, many accounts describe those on board as remaining orderly.

Efforts to launch lifeboats were largely unsuccessful. Inexperienced personnel, the angle of the sinking ship, and mechanical difficulties led to lifeboats capsizing or being damaged. Several nurses and soldiers were killed during these attempts. It is believed that Margaret Rogers lost her life in this phase of the evacuation.

Ten New Zealand nurses and 22 men from the New Zealand Medical Corps and No. 1 Stationary Hospital died.

Survivors spent several hours in the water, exposed to cold conditions and exhaustion. Some clung to wreckage; others assisted colleagues unable to swim. Rescue vessels, including British and French destroyers, arrived later in the day. Six days later,on the 29th October, all surviving nurses and some medical officers returned to Alexandria on the hospital ship, the Grantully Castle.

Image source: https://ww100.govt.nz/no-ordinary-transport-the-sinking-of-the-marquette

Aftermath

The sinking of the Marquette led to outrage about the decision to transport medical personnel on a vessel carrying ammunition and troops rather than on a hospital ship. Marked with a red cross, hospital ships could sail with a much greater degree of safety with the protection of the Geneva Convention. The troopship was, for German submarines, a valid target.

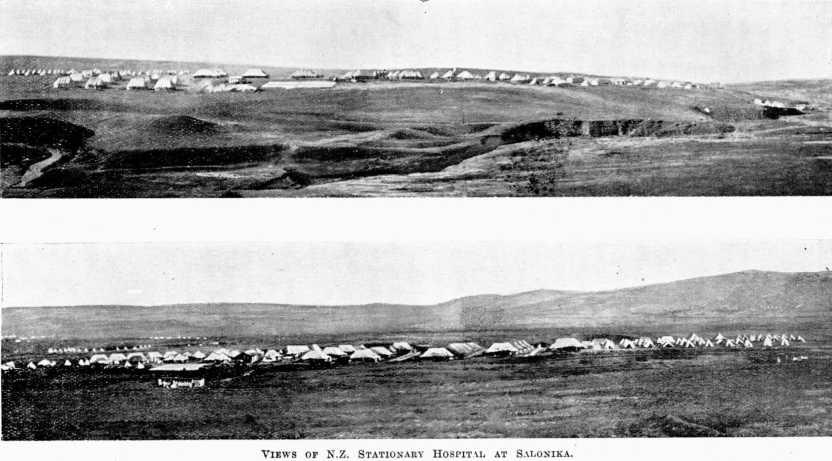

One can only imagine the emotions of the survivors as they undertook the journey to Salonika again later in the year in order to establish a tented hospital at Lembet Camp. The hospital was in operation until March 1916, when it left for France.

Image source: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/photo/1st-new-zealand-stationary-hospital

In Memory

Margaret Rogers is buried at the Mikra British Cemetery at Kalamaria where there is a memorial to the loss of the Marquette.

Margaret is also listed on the war memorial at Akaroa where her father lived.

Image source: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/memorial/akaroa-war-memorial

Margaret and the other nine nurses lost in the Marquette sinking are remembered at the Nurses’ Memorial Chapel at Christchurch Hospital and at the Marquette Nurses’ Memorial at Waimate.

The events of 23 October 1915 are also dramatised in the Australian TV series, ANZAC Girls, which until December 31st, 2025 is freely available to view here.

Image Source: Episode 3, https://player.stv.tv/summary/all3-anzac

Footnote

Wreckage of the Marquette was found in May 2009 by a Greek dive team. It rests in 87 metres of water of the Thermaikos Gulf in the North Aegean Sea. A protection order for the wreck has been sought by The British Embassy in Greece.

Reference Links

- https://www.armymuseum.co.nz/2023-today-in-history-marquette-sinking/

- https://ww100.govt.nz/no-ordinary-transport-the-sinking-of-the-marquette

- https://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/video/marquette-great-war-story

- https://ww100.govt.nz/no-ordinary-transport-the-sinking-of-the-marquette

- https://www.cnmc.org.nz/the-marquette/

- https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/287792/%27all-of-a-sudden-there-was-this-bang%27

- https://www.cnmc.org.nz/resources/museum/prentice-papers/

Screening in London: ‘By Far Kaymakchalan’ – A Documentary by Bojan Pajic

Those in London, or able to visit, on Saturday 18 October are warmly invited to attend the screening of By Far Kaymakchalan, a newly completed documentary by Australian writer and historian Bojan Pajic. The one-hour film will be shown from 3:00 to 5:00 pm in Room KIN 204, King’s College London, King’s Building, Strand Campus, WC2R 2LS.

Bojan Pajic is the author of two books examining the experiences of Australians and New Zealanders who served with Serbian forces during the First World War. By Far Kaymakchalan builds on his previous work and combines archival material, personal testimonies, and historical analysis to illuminate the shared history of these Allied nations. The event, hosted by Dr Stephen Morgan, Lecturer in Film Studies at King’s College London, will be followed by a discussion with Bojan Pajić.

Filmed in Australia, Serbia, Greece, and North Macedonia over a period of eighteen months, By Far Kaymakchalan is based on Pajić’s research that has revealed that more than 1,500 Australian and New Zealand volunteer doctors, nurses, ambulance drivers, soldiers, sailors, and aircrew served alongside Serbian forces during the war.

Full details of the event are available via this link.

NB For security reasons, King’s College London requires a list of attendees to be submitted 24 hours in advance. If you are thinking of attending, please don’t forget to register beforehand.

This screening offers a rare opportunity to engage with a significant and often overlooked chapter of First World War history, and to hear directly from the researcher and filmmaker who has dedicated much of his work to bringing these stories to light.

I’m very grateful to Jon Lewis, author of the excellent The Forgotten Front; the Macedonian Campaign 1915 – 1918, for bringing this to the attention of the Society – thanks Jon!

See also: https://salonikacampaignsociety.org.uk/2020/09/26/australians-and-new-zealanders/

Pte George Excell of Wotton-under-Edge

One of the things I enjoy most about living in the county of Gloucestershire is its beautiful countryside and many wonderful walks. After a recent hike involving some strenous Cotswold climbs, I stopped for refreshments and recovery in Wotton-under-Edge. Of course, I had to take in the Wotton war memorial where I later discovered a Salonika connection…

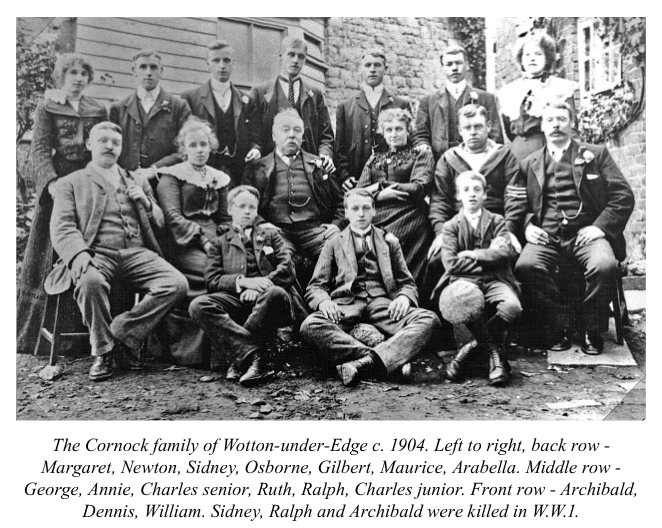

According to the town’s heritage centre, the memorial was erected in 1920 and unveiled by a Mrs Cornock. Apparently, and tragically, eight of her sons served in WWI – three did not return*. Among the names on the memorial is that of George Edward Excell.

George Edward Excell was born in 1896 in Wotton-under-Edge, one of six children of Edwin and Elizabeth Excell, who lived in the Sinwell area of the town. His father, Edwin, worked as a rural postman, while his mother, Elizabeth served as matron at the Perry & Dawes Almshouses on Church Street, Wotton. Edwin died while George was still young.

After finishing school, George began working for Mr. G. W. Palmer, a boot maker based on Long Street in Wotton. Mr. Palmer later served in the Royal Naval Division as an Able Seaman during the Great War.

At the outbreak of the war, George enlisted in Wotton, joining the 11th Battalion of the Worcestershire Regiment with the service number 18644. The battalion was formed on 14 September 1914 as part of the 78th Brigade in the 26th Division. They trained in Wiltshire, including at Sherrington and on Salisbury Plain, before landing in Boulogne on 21 September 1915. Over the next two years, George saw extensive action on the front lines and was wounded twice.

George Excell recovered from his wounds and resumed service with the Worcestershire Regiment. In September 1918, the 11th Battalion of the Worcesters, including George, was deployed to the Salonika front.

On 16th October 1918, George’s mother, Elizabeth Excell, received a telegram stating that her son was dangerously ill in a hospital in Salonika. Tragically, George had already died of pneumonia four days earlier. It wasn’t until Saturday, 19th October, that she received confirmation of his death. George Excell was 22 years old.

George is buried at Doiran Military Cemetery, in Plot 5, Row H, Grave 28.

Source: ‘First World War Heroes of Wotton-under-Edge’ by Bill Griffiths available online here.

*Bill Griffiths’ book also includes this picture of the Cornock family and the three sons that never returned to Wotton-under-Edge.

Now online – Nick Ilic’s lecture on Sir Thomas Lipton and Serbia during WW1

On 9th February Colonel (Retd) Nick Ilic gave an online talk about Sir Thomas Lipton (1848–1931), the Scottish businessman and philanthropist best known for founding the Lipton tea company. I wrote an introduction to the talk here.

I’ve just spotted, rather belatedly, that Nic’s talk is now available on YouTube.

Nick Ilic lecture on Sir Thomas Lipton and Serbia during WW1

Sir Thomas Lipton (1848–1931) was a Scottish businessman and philanthropist best known for founding the Lipton tea company, which became one of the largest tea brands in the world. He was also a noted sportsman, famously competing in the America’s Cup yacht races several times, and made significant contributions to charity and education throughout his life.

During World War I, Lipton visited Serbia to offer humanitarian aid, moved by the suffering caused by the conflict. Recognizing the dire need for medical support, he donated substantial funds and medical supplies to assist Serbian soldiers and civilians, especially during the devastating 1915 retreat. His efforts helped establish field hospitals and provided relief to those affected by both the war and the widespread disease in the region.

This remarkable, and to me at least, largely forgotten story will be told with much more skill and knowledge by Colonel (Retd) Nick Ilic in a free online talk this week. As Nick explains, “It is a fascinating story and I’ve assembled a large number of photographs to try and bring it to life.”

The talk is on 11 February at 7pm and should last about an hour. You can join via this link:

- Join Zoom Meeting https://us06web.zoom.us/

- Meeting ID: 837 1461 6886 Passcode: 327477

Update !

Nick’s talk is now available on YouTube

Battling ‘General Malaria’ on the Macedonian front, 1915–1919

I’m grateful to SCS member Nick Palmer for bringing this online article (Battling ‘General Malaria’ on the Macedonian front, 1915–1919) to my attention. It’s a very recent publication from Dr Laura Robson-Mainwaring at the National Archives.

The article takes a look at some of the medical case sheets from the 28th General Hospital, Salonika to reveal the impact of malaria and the efforts to counteract it; from quinine and mosquito nets, to importing fish to eat mosquito larvae!

The impact of the disease is considered at the macro level – and, poignantly, at the individual level through the sad record of Isaac Jones of the South Wales Borderers who caught malaria in May 1918 with recurring attacks over the next few months before his death on 14 September 1918.

Remembering…

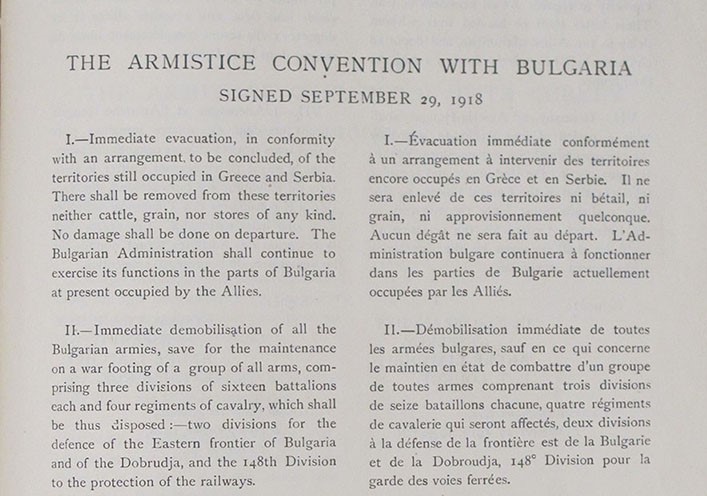

It is a very appropriate day and time (this is posted at noon), to be thinking about the contribution and ordeal of those working and fighting in Salonika – as it was at midday on this day, 106 years ago, that the Armistice of Salonica came into force, having been signed the day before.

Dr Isobel Tate

‘X’ (formerly Twitter) is not a favourite medium of mine but it can, in some circumstances, be an informative and interesting forum. In the past year the Society has set up an account and we have managed to both share and learn from this online community. For example, in a series of posts, @DanielJPhelan (Speaker, tour guide, & EOHO volunteer for @CWGC ) shared a thread about a discovery while on holiday in Malta. During his stay, Dan visited Pieta Military Cemetery and it was there that he found the grave of Dr Isobel Tate.

On his return home, Dan researched and shared his findings in a series of posts and images on X (Twitter). Thanks Dan for sharing your research!

“Isobel Addey Tate was born, around 1874, in Country Armagh, Northern Ireland. At a time when female doctors were rare, she studied medicine at Queens University, Belfast graduating in 1899. Continuing her studies, she qualified as a Doctor of Medicine in 1902.

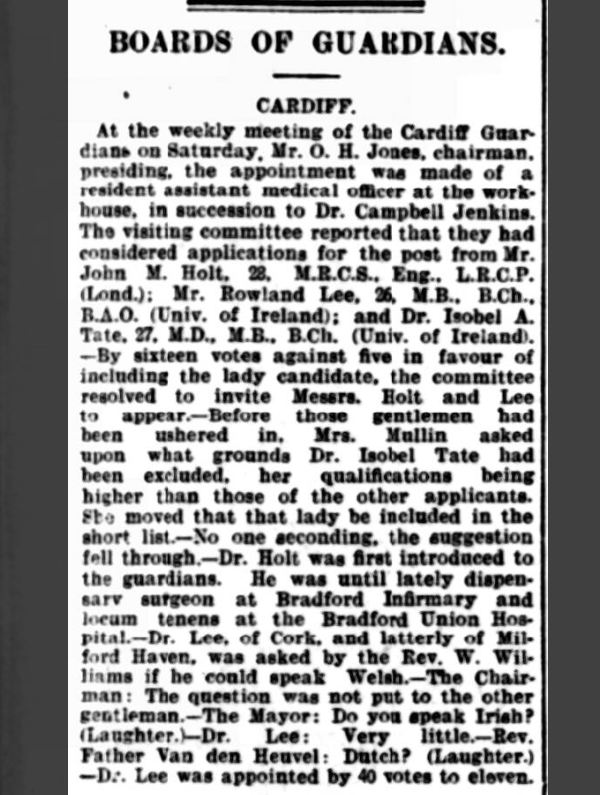

After qualifying, a huge achievement, she moved to England and held a number of positions in hospitals and medical institutions. However, it seems pursuing her career in medicine was not easy…

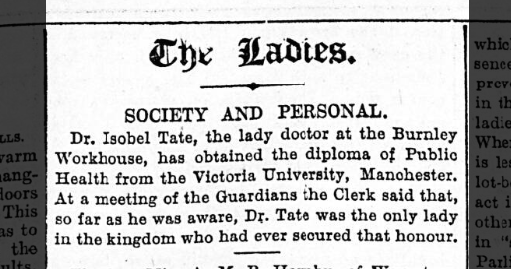

In 1904, while working at the Burnley Workhouse, Dr Tate obtained a Diploma in Public Health from Victoria University, Manchester. It was thought at the time that Dr Tate was the only lady in the kingdom who had ever secured that honour.

In 1915, with the Great War being fought, Dr Tate volunteered to serve with the Serbian Relief Fund. The relief fund was set up and commanded by Mrs Mabel St Clair Stobart. It had seven women surgeons and doctors, which included Dr Tate.

While serving with the Serbian Relief Fund, Dr Tate contracted typhoid and returned home to convalesce. Once well again she became a radiographer at Graylingwell War Hospital, near Chichester. Feeling she ‘was not doing enough’ Dr Tate offered to go abroad again.

Isobel Tate volunteered for service with RAMC and embarked for Malta in August 1916. In Malta she treated sick and wounded servicemen, including casualties from Gallipoli and Salonika. While working at Valletta Military Hospital she became ill. Sadly, on 28th January 1917, Dr Isobel Tate succumb to her illness and died of typhoid fever.

The funeral of Dr Isobel Tate took place on Tuesday 30th January 1917. Her flag-draped coffin was carried by medical officers, flanked by two lines of wreath carrying NCOs from the RAMC. The firing party contained 40 men of the Royal Garrison Artillery. A lengthy train of medical officers, officers from other units, and local members of the medical profession followed her coffin. At the graveside assembled ‘lady doctors’, principal matron, matrons, sisters, and nurses, from all hospitals and camps on the island.

It’s incredible to think that Isobel Addey Tate lived, served, and achieved so much, in an era before women even had the vote. I think this quote from a newspaper at the time is very fitting.”

You can read the complete thread from Dan on Twitter @DanielJPhelan:

The nature of ‘social media’ does not really allow for detail and detailed discussion, so Dan’s account of Isobel Tate’s life is necessarily short. If you would like to read more about her life, and the challenges she and other women faced, there is a more in-depth examination here.

Memorial Service and Talk

The ‘Ninth Annual Memorial Service for Women in Foreign Medical Missions in the Great War’ takes place on Saturday 18th February 2023.

The event takes from 11:00 -14:30 at the Serbian Orthodox Church of St Sava

89 Lancaster Rd, London W11 1QQ with speakers Colonel Nick Ilic, the former British Defence Attaché in the Embassy in Belgrade, and Zvezdana Popovic.

- 11.00 – Memorial Service in The Serbian Orthodox Church of St Sava

- 13.00 -14.30 – Refreshments and Talk in the Bishop Nikolaj Community Centre

The occasion will also feature a talk about the legacy of Dr Elsie Inglis, Scottish Women’s Hospitals and women in other foreign medical missions in Serbia, Corfu, Vido and the Salonika Front after the death of Dr Inglis.

If you would like to attend, RSVP via: info@serbiancouncil.org.uk

You can download the event poster below:

Featured image source: Wikipedia