Last year I resolved to share the story of the sinking of the hospital ship, Rewa. I decided to do this on the anniversary of the event in 2026. The trouble was, I failed to check the date and, convinced that it was in February, by the time I looked up the details I realised I had missed it – 4 January! I could have left it until 2027 but, instead, decided to post the story today, Fred Braysher’s birthday, as it was Fred (my grandfather) who told me the story 44 years ago.

Continue reading “The Sinking of the Rewa”Category: Faces of Salonika

A series of images of those – from all sides – who took part in, or witnessed, the First World War campaign in Macedonia from 1915 to 1918.

Happy Year of the Horse!

Once again it’s time to celebrate the Lunar New Year – or Spring Festival, if you prefer – and this time it’s the ‘Year of the Horse’, which makes finding a Salonika-related photo remarkably easy! Before we look at that, it’s worth noting that in 2026 it’s a ‘Fire Horse’, something we haven’t seen since 1966. Apparently, after an introspective ‘Year of the Snake’, we are now galloping forward with vibrant and fiery energy, which symbolises adventure, vitality, and momentum. So hold onto your hat!

Continue reading “Happy Year of the Horse!”Mettle and Steel: the AANS in Salonika

Searching for information recently about nursing in Salonika, I stumbled across Mettle and Steel: the AANS in Salonika. It’s an account of the punishing nature of Australian military nursing in Salonika. From 1917, Australian nurses were sent into this difficult and unfamiliar theatre of war to relieve the British, French and Canadian nurses and to provide nursing care to British soldiers and prisoners of war. As nursing ‘our boys’ was a major motivation for overseas service, it was something of a disappointment for many that they could not nurse Australian soldiers.

A group of Australian Army nurses about to depart from Adelaide for Salonica, 14 June 1917. From the left: Miss Molly Wilson, Mrs J. Tyers, Miss Edith Horton, Miss Marion Geddes, Miss Laura Begley, Mrs Jessie McHardie White (Principal Matron), Mrs Forsyth (wife of General Forsyth), Miss Violet Mills (Matron of No 5 Australian General Hospital who was on a visit to Adelaide), Miss Alice Prichard and Miss Florence G. Gregson.

I hadn’t quite appreciated the scale and complexity of the Australian nursing presence: four contingents were dispatched via Egypt, under constant U-boat threat, and then distributed across a shifting network of British hospitals in Greece and the surrounding hills. Each unit was allocated one Matron, ten AANS Sisters and eighty Staff Nurses. The nurses were led by senior matrons such as Jessie McHardie White, who oversaw not only clinical standards but the welfare and morale of hundreds of nurses. Staff Nurse Lucy May’s personal account helps convey the experience of Salonika in winter:

[12 October 1917] Water racing thru wards & reached halfway up bedsteads, haversacks, boots, socks, pants floating down road…

[21 October] Lanterns blowing out & leaving you in dark…

[23 October] Still don weather attire, only wearing men’s pyjama pants, putties, gum boots, man’s shirt also. Had dress tucked around waist all night…

[2 November] Imagine me [on night duty] over my ankles in mud, dragging one foot out then other foot & standing on one leg in grim peril or sitting down hastily…feeling the rain oozing through my mack. This is the life?”

As winter ended, the nurses then faced oppressive summers dominated by malaria. The AANS uniform was adapted in an attempt to counter the mosquito risk. A ‘mosquito proof’ nurse would be clad in her working dress, huge gloves, rubber boots and thick veil which, according to Lucy Tydvil Armstrong:

“made it quite impossible to carry out our duties, when men were rigoring and vomiting all night long, we just had to do away with the precautions, & run the risk of being bitten with mosquitos.”

A group of Australian Army Nursing Service nurses at the 52nd British General Hospital at Kalamaria, Greece ready for night duty wearing headdress provided for protection against mosquitoes. C 1918.

Despite the precautions, Matron McHardie White later reported that, ‘most of the nurses were affected by it [malaria] one time or another…’ By August 1918 45 nurses had been sent back to Australia from Salonika and another 14 were waiting to go, mostly on grounds of ill health. The death of Sister Gertrude Evelyn Munro in 1918 underlines the very real cost of the AANS service.

Sisters Gertrude Evelyn Munro and Amy Christie of the AANS. The photograph was probably taken at the 60th British General Hospital, Salonica.

Despite deteriorating health and official doubts about the value of their continued presence, the nurses remained in Salonika until after the war ended, not returning home until early in 1919. Their courage and professionalism were acknowledged through praise and decorations from British, Serbian and Greek authorities. Matron McHardie White, as just one example, was awarded the Serbian decoration of the Order of St Sava and was made a Member of the British Empire.

Nurses’ Narratives

It’s always interesting to read first-hand accounts of experience and so it was good to see that some diary and retrospective narratives written by the AANS nurses have been, and are being, transcribed. Staff Nurse Vivian A Lee Shea, for example, recalled,

We arrived in the midst of summer & the height of the Malaria & Dysentry season, & work commenced right away. We had much to learn. We were all new to each others ways & the medical Staff & personnel had only just landed as we ourselves had.

The Hospital was rather well situated at an elevation of about 2000 ft above sea level & this gave us a cooler summer, but made it impossible to live there in the winter months. During the winter months we occupied the Prisoners of War Hospital in the Base area. Here we nursed British Troops, as well as prisoners of War, the latter were representatives from practically every one of the Baltic States. Germans Bulgars, Turks, Romanians, Greeks Albanians & Serbs, in fact any one found in enemy lines.

Annie E Major-West remembered,

We remained in Salonika till February 1919, during the whole time the work was very heavy at times the hours on duty were particularly long. these conditions were occasioned by the prevalence of Sickness amongst the Sisters and Medical Officers.

Frequently the Bulgars & Germans were over in Planes endeavouring to bomb

the Town but the Vicinity of the Hospital was never damaged, during the Month

of August 1917 the town was partially destroyed by fire, Supposed to have

been the work of Spies.

- Read the full article Mettle and Steel: the AANS in Salonika.

- Search for first hand accounts here: https://transcribe.awm.gov.au/transcription

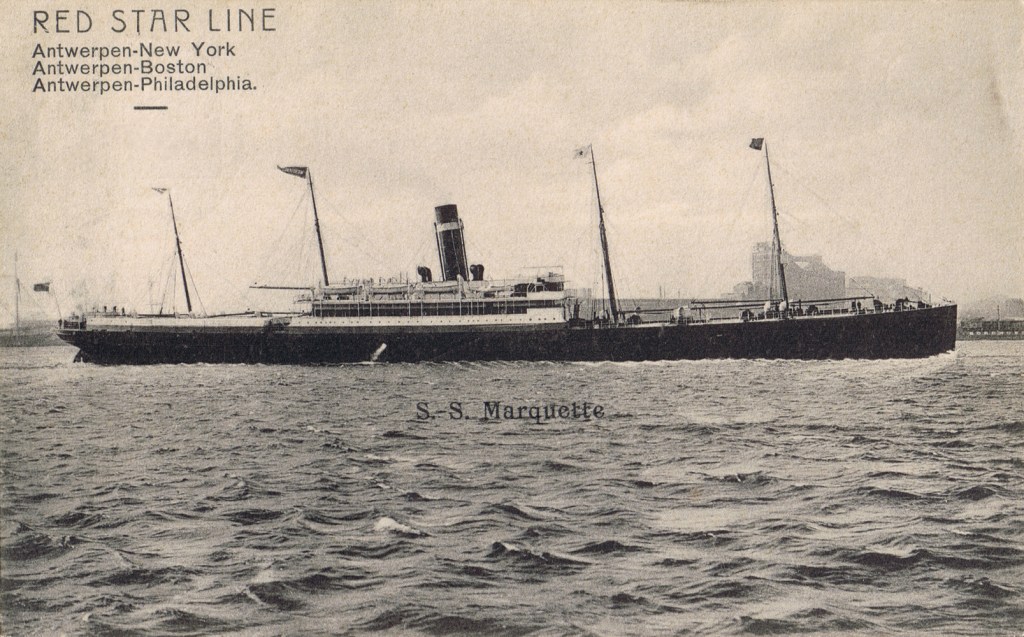

The Sinking of the Marquette, 1915

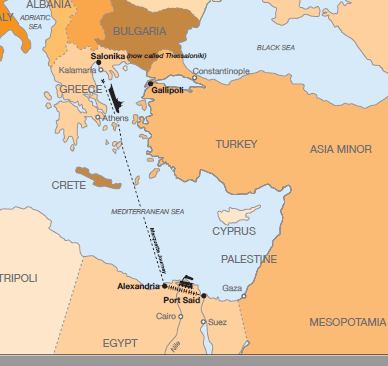

A little over 110 years ago, on Saturday 23 October 1915, the British transport ship Marquette was torpedoed by the German submarine U-35 as it entered the Gulf of Salonika. The ship sank within ten minutes. Of the 741 people on board, 167 died, including 32 New Zealanders – ten of whom were nurses.

The New Zealand Nurses

Most of the New Zealanders aboard were members of the 1st New Zealand Stationary Hospital. They had been serving in Egypt, treating casualties from Gallipoli, and were being transferred to support Allied operations in the Balkans. Among them was Staff Nurse Margaret Rogers, who had enlisted only months earlier in July. Indeed, The New Zealand Army Nursing Service was itself new and only established early in 1915.

Image source: Nurse Margaret Rogers, URL: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/photo/nurse-margaret-rogers, (Manatū Taonga — Ministry for Culture and Heritage), updated 28-May-2024

The Marquette, originally a cargo vessel, had been adapted for wartime transport.

Image source: https://ww100.govt.nz/no-ordinary-transport-the-sinking-of-the-marquette

When it departed from Alexandria on 19 October, it carried medical personnel, British troops, over 500 mules, and ammunition. Although accompanied by a French destroyer during part of the journey, the escort departed the day before the attack.

At approximately 9:15 a.m., witnesses reported sighting a torpedo shortly before it struck the starboard side of the ship. The impact caused the vessel to list sharply. Despite the suddenness of the event, many accounts describe those on board as remaining orderly.

Efforts to launch lifeboats were largely unsuccessful. Inexperienced personnel, the angle of the sinking ship, and mechanical difficulties led to lifeboats capsizing or being damaged. Several nurses and soldiers were killed during these attempts. It is believed that Margaret Rogers lost her life in this phase of the evacuation.

Ten New Zealand nurses and 22 men from the New Zealand Medical Corps and No. 1 Stationary Hospital died.

Survivors spent several hours in the water, exposed to cold conditions and exhaustion. Some clung to wreckage; others assisted colleagues unable to swim. Rescue vessels, including British and French destroyers, arrived later in the day. Six days later,on the 29th October, all surviving nurses and some medical officers returned to Alexandria on the hospital ship, the Grantully Castle.

Image source: https://ww100.govt.nz/no-ordinary-transport-the-sinking-of-the-marquette

Aftermath

The sinking of the Marquette led to outrage about the decision to transport medical personnel on a vessel carrying ammunition and troops rather than on a hospital ship. Marked with a red cross, hospital ships could sail with a much greater degree of safety with the protection of the Geneva Convention. The troopship was, for German submarines, a valid target.

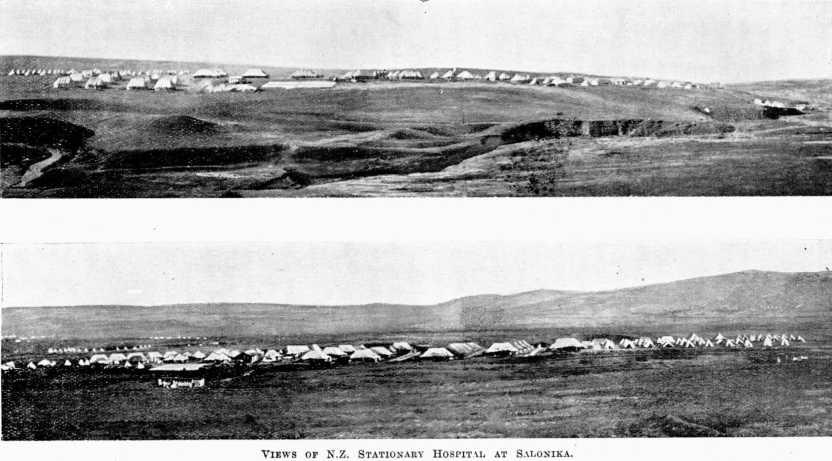

One can only imagine the emotions of the survivors as they undertook the journey to Salonika again later in the year in order to establish a tented hospital at Lembet Camp. The hospital was in operation until March 1916, when it left for France.

Image source: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/photo/1st-new-zealand-stationary-hospital

In Memory

Margaret Rogers is buried at the Mikra British Cemetery at Kalamaria where there is a memorial to the loss of the Marquette.

Margaret is also listed on the war memorial at Akaroa where her father lived.

Image source: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/memorial/akaroa-war-memorial

Margaret and the other nine nurses lost in the Marquette sinking are remembered at the Nurses’ Memorial Chapel at Christchurch Hospital and at the Marquette Nurses’ Memorial at Waimate.

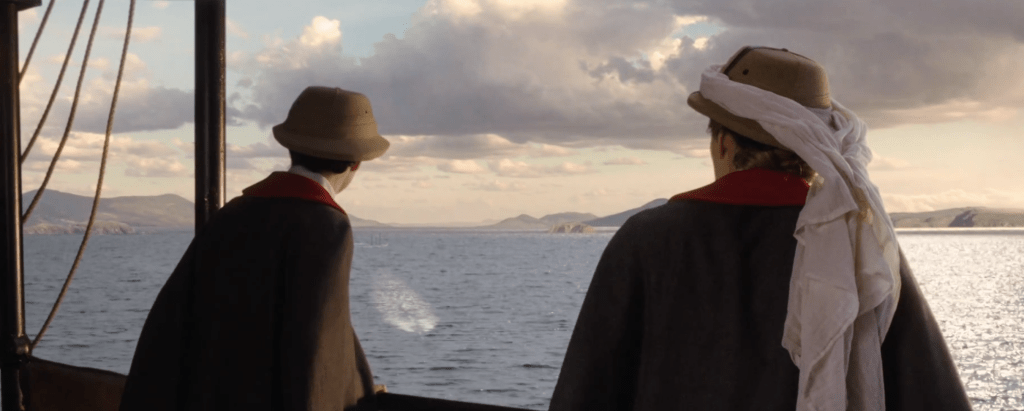

The events of 23 October 1915 are also dramatised in the Australian TV series, ANZAC Girls, which until December 31st, 2025 is freely available to view here.

Image Source: Episode 3, https://player.stv.tv/summary/all3-anzac

Footnote

Wreckage of the Marquette was found in May 2009 by a Greek dive team. It rests in 87 metres of water of the Thermaikos Gulf in the North Aegean Sea. A protection order for the wreck has been sought by The British Embassy in Greece.

Reference Links

- https://www.armymuseum.co.nz/2023-today-in-history-marquette-sinking/

- https://ww100.govt.nz/no-ordinary-transport-the-sinking-of-the-marquette

- https://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/video/marquette-great-war-story

- https://ww100.govt.nz/no-ordinary-transport-the-sinking-of-the-marquette

- https://www.cnmc.org.nz/the-marquette/

- https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/287792/%27all-of-a-sudden-there-was-this-bang%27

- https://www.cnmc.org.nz/resources/museum/prentice-papers/

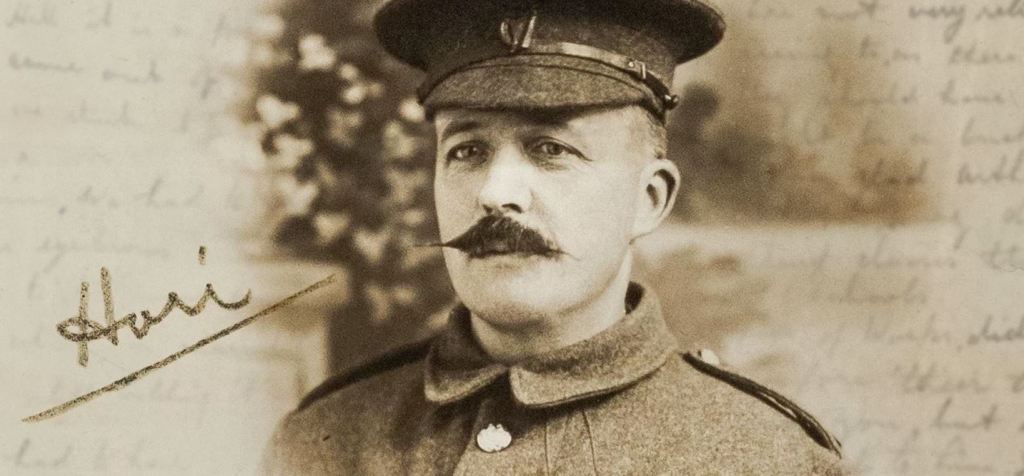

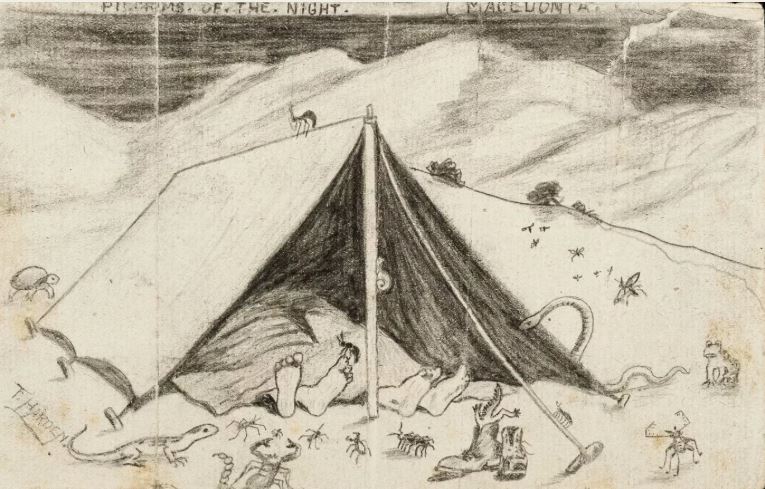

Remembering Hori Tribe (1877-1917)

I’ve only recently discovered a fascinating and beautifully presented online exhibition commemorating the life of Hori Tribe (1877-1917), an employee of The Royal Parks who served in Salonika before transferring to the Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) in June 1917.

The exhibition, co-curated by the Royal Parks and Hori’s great-granddaughter, Sarah Gooch, has a wonderful and moving collection of photos, drawings and extracts from Hori’s letters.

I certainly won’t attempt to retell Hori’s story here, instead I recommend a visit to the digital exhibition. It is definitely worth a visit and a few moments of your time.

With the EEF since June and now, at the start of December 1917, Hori had two days’ rest at a monastery just outside of Jerusalem. In the final letter he sent home, Hori included some rosemary – associated with remembrance:

‘The pieces of rosemary included I picked from a hedge in the grounds of the monastery.’

Hori spent two days at the monastery just before his last battle.

Hori was killed in action on 8 December 1917. He is laid to rest at the Jerusalem War Cemetery.

Remembering Hori Tribe – A digital exhibiton celebrating the life of Hori Tribe (1877-1917), an employee of The Royal Parks who was killed in action during the First World War.

Pte George Excell of Wotton-under-Edge

One of the things I enjoy most about living in the county of Gloucestershire is its beautiful countryside and many wonderful walks. After a recent hike involving some strenous Cotswold climbs, I stopped for refreshments and recovery in Wotton-under-Edge. Of course, I had to take in the Wotton war memorial where I later discovered a Salonika connection…

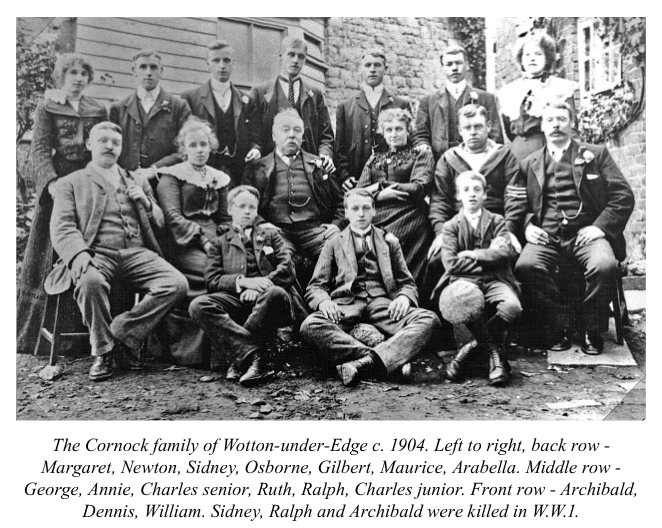

According to the town’s heritage centre, the memorial was erected in 1920 and unveiled by a Mrs Cornock. Apparently, and tragically, eight of her sons served in WWI – three did not return*. Among the names on the memorial is that of George Edward Excell.

George Edward Excell was born in 1896 in Wotton-under-Edge, one of six children of Edwin and Elizabeth Excell, who lived in the Sinwell area of the town. His father, Edwin, worked as a rural postman, while his mother, Elizabeth served as matron at the Perry & Dawes Almshouses on Church Street, Wotton. Edwin died while George was still young.

After finishing school, George began working for Mr. G. W. Palmer, a boot maker based on Long Street in Wotton. Mr. Palmer later served in the Royal Naval Division as an Able Seaman during the Great War.

At the outbreak of the war, George enlisted in Wotton, joining the 11th Battalion of the Worcestershire Regiment with the service number 18644. The battalion was formed on 14 September 1914 as part of the 78th Brigade in the 26th Division. They trained in Wiltshire, including at Sherrington and on Salisbury Plain, before landing in Boulogne on 21 September 1915. Over the next two years, George saw extensive action on the front lines and was wounded twice.

George Excell recovered from his wounds and resumed service with the Worcestershire Regiment. In September 1918, the 11th Battalion of the Worcesters, including George, was deployed to the Salonika front.

On 16th October 1918, George’s mother, Elizabeth Excell, received a telegram stating that her son was dangerously ill in a hospital in Salonika. Tragically, George had already died of pneumonia four days earlier. It wasn’t until Saturday, 19th October, that she received confirmation of his death. George Excell was 22 years old.

George is buried at Doiran Military Cemetery, in Plot 5, Row H, Grave 28.

Source: ‘First World War Heroes of Wotton-under-Edge’ by Bill Griffiths available online here.

*Bill Griffiths’ book also includes this picture of the Cornock family and the three sons that never returned to Wotton-under-Edge.

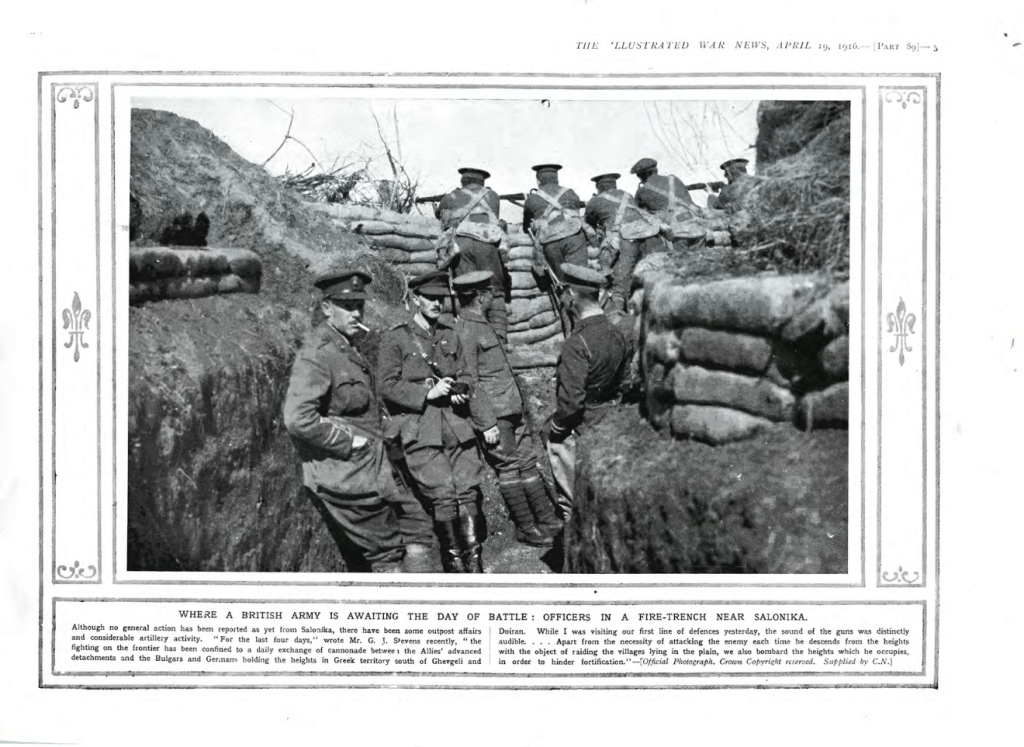

The Illustrated War News – April, 1916

Photographs from Salonika featured quite strongly in “The Illustrated War News” of April 19th, 1916. Here are a couple of those photos:

More to follow in the next few days.

Now online – Nick Ilic’s lecture on Sir Thomas Lipton and Serbia during WW1

On 9th February Colonel (Retd) Nick Ilic gave an online talk about Sir Thomas Lipton (1848–1931), the Scottish businessman and philanthropist best known for founding the Lipton tea company. I wrote an introduction to the talk here.

I’ve just spotted, rather belatedly, that Nic’s talk is now available on YouTube.

‘Topical Budget’ – newsreels

Topical Budget was one of the biggest British newsreels during the silent film era, competing with Gaumont Graphic and Pathé Gazette. It was produced by William Jeapes’ Topical Film Company and first released in 1911. Although several newsreels existed at the time, only Topical, Gaumont, and Pathé remained by the middle of World War I.

Topical had fewer resources than its competitors, and it might not have survived if not for a deal with the War Office, which needed an outlet for its official war films. In 1917, the War Office Official Topical Budget was launched, giving the newsreel exclusive footage from the front lines. Later that year, the War Office Cinematograph Committee (WOCC) bought the Topical Film Company, turning the newsreel into a useful propaganda tool.

After the war, the newsreel once again became the Topical Budget under the ownership of newspaper magnate Edward Hulton. Finally, never having adopted sound, the newsreel ceased production in March 1931.

A significant portion of Topical Budget’s wartime footage is preserved at the Imperial War Museum (IWM), where, after a little searching, you can discover many fascinating films from the Salonika Front.

Object description (IWM)

British troops, mainly 22nd Division, on the Salonika Front, 1917-1918 (?).

Full description (IWM)

(Reel 1) Wounded soldiers with mule transport, snow-covered mountains filmed from an aircraft (Mount Olympus ?). A 13-pounder anti-aircraft gun showing the rangefinder in use. A British Army camp, with a bakery and soldiers washing and eating. Three soldiers in a trench fusing Mills grenades. A Royal Engineers wagon laying a line. A view from the rear gunner’s position of a two-seater aircraft taking off, flying over Salonika harbour, the nearby mountains, and a military camp. (Reel 2) Brigadier-General F S Montague-Bates (66th Brigade, 22nd Division) in a posed position. A return shot of the three soldiers fusing Mills grenades. They change to fitting magazines on Lewis machine guns and using a trench periscope. General Guillaumat inspects a British battalion. General scenes of the British Army camp. A Red Cross wagon on the move. A heavily camouflaged gun (possibly a 60-pounder) and a 6-inch howitzer. More soldiers in trenches. Major-General J Duncan, commanding 22nd Division, and Lieutenant-General H F M Wilson posed together. British soldiers at bayonet practice. (Reel 3) A Highland battalion, probably Black Watch, with its pipe band, and a single piper playing. A French general decorates British troops, who march past.

Video source, all rights acknowledged

Nick Ilic lecture on Sir Thomas Lipton and Serbia during WW1

Sir Thomas Lipton (1848–1931) was a Scottish businessman and philanthropist best known for founding the Lipton tea company, which became one of the largest tea brands in the world. He was also a noted sportsman, famously competing in the America’s Cup yacht races several times, and made significant contributions to charity and education throughout his life.

During World War I, Lipton visited Serbia to offer humanitarian aid, moved by the suffering caused by the conflict. Recognizing the dire need for medical support, he donated substantial funds and medical supplies to assist Serbian soldiers and civilians, especially during the devastating 1915 retreat. His efforts helped establish field hospitals and provided relief to those affected by both the war and the widespread disease in the region.

This remarkable, and to me at least, largely forgotten story will be told with much more skill and knowledge by Colonel (Retd) Nick Ilic in a free online talk this week. As Nick explains, “It is a fascinating story and I’ve assembled a large number of photographs to try and bring it to life.”

The talk is on 11 February at 7pm and should last about an hour. You can join via this link:

- Join Zoom Meeting https://us06web.zoom.us/

- Meeting ID: 837 1461 6886 Passcode: 327477