… is Sandham Memorial Chapel! That’s the opinion of Rachel Morley, Director of Friends of Friendless Churches. She was a guest of the podcast series, The Rest Is History, presented by historians Tom Holland and Dominic Sandbrook on 13 September. Rachel’s task was to list her top ten British churches, which is quite a task given that there are more than 16,000 in England alone!

Continue reading “The 4th best church in the UK …”Tag: Medical Services

The medical services and their activities in the Macedonian Campaign of 1915-1918.

Two sisters of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals

The Society has received an enquiry about two sisters who served with the Scottish Women’s Hospitals in the Balkans. If you can help with this, please either add a comment to this post or use the ‘Contact Us’ form.

Continue reading “Two sisters of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals”Stretcher-bearers

I was listening a while ago to an oral history on the Imperial War Museum’s site from an unnamed British stretcher bearer on the Struma Front. He may have been forgotten but he lives alongside more remembered company in the form of composer Ralph Vaughan Williams and artist Stanley Spencer, both of whom served as stretcher-bearers in the campaign.

The Great War Stories: Luton’s Greatest has an account by Private Robinson who in Gallipoli, faced challenges that stretcher-bearers in Salonika would have found very similar,

“People have no idea what difficulties and dangers have to be overcome in evacuating wounded. The hilly nature of the country does away with the idea of mechanical transport, and every case has to be carried to other hospitals on the beach on stretchers.”

Perhaps it’s because many conscientious objectors signed up for medical, rather than military service, that many accounts of the lives and work of stretcher-bearers have not survived. Maybe, but that’s just speculation on my part… However, one set of diaries has not only survived but been re-discovered by author Sara Woodall, great-niece of the author of the diaries.

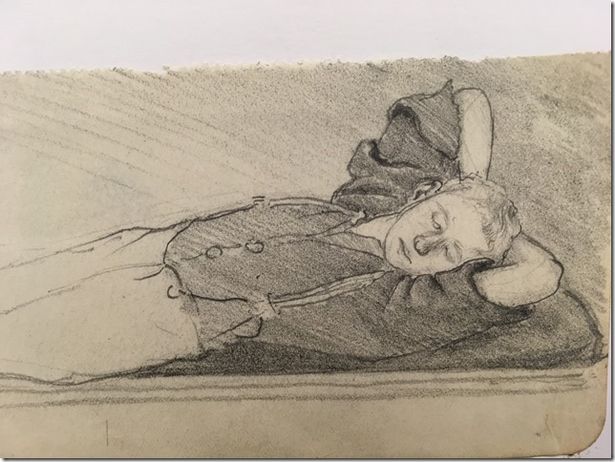

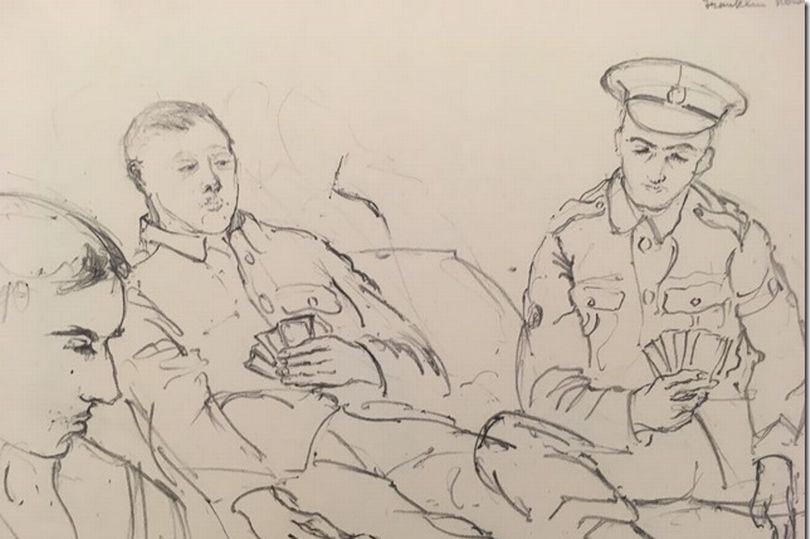

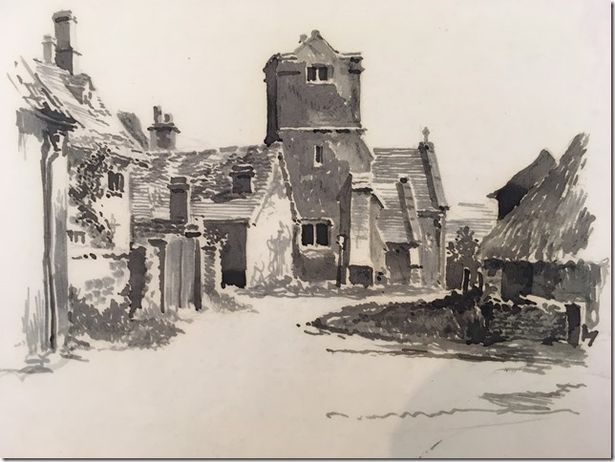

Sara discovered her great-uncle’s diaries while at home in Cambridge and was astounded to find both written accounts and accomplished illustrations. The author of these diaries was Bernard Eyre Walker, a stretcher-bearer for the British Expeditionary Force and later one of Cumbria’s leading painters.

The existence of the diaries is something of a miracle in itself. Forced to retreat by a German attack, Bernard had to abandon the diaries in a field hospital. The diaries were later picked up by a German soldier and taken to Belgium, before eventually making their way home to Bernard in Keswick.

Illustrations by Bernard Eyre Walker from his war-time diaries.

Sara has edited and published the diaries, complete with 140 of Bernard’s illustrations from the trenches. I haven’t read the diaries myself, and it’s not an account of stretcher- bearers in Salonika, but it’s a primary source of a largely unrecorded aspect of the time and likely to have a wide appeal. There’s more about the book here.

The book is available on amazon.co.uk or you can order it directly from Sara at jdt.woodall@btopenworld.com or from the address below.

A Voice From the Trenches 1914-1918 From the Diaries and Sketchbooks of Bernard Eyre Walker. Edited by Sara Woodall. Price £19.95 (+ £3.10 p&p) from Sara Woodall, 17 High Street, Great Eversden, Cambridge, CB23 1HN

Great War Huts – Hospital Blues

The latest video offering from the excellent Great War Huts seems particularly relevant to the Salonika campaign – Hospital Blues: The British Hospital Uniforms of the First World War. Given the high sickness rates in the BSF, not to mention wounds and accidents, many men would have found themselves in hospital blues.

Continue reading “Great War Huts – Hospital Blues”Remarkable Women of the Salonika Campaign

One of the better known aspects of the Salonika campaign is the role of the remarkable women of the Scottish Women’s Hospital – particularly the assistance they gave to the Serbians – and of other women volunteers and medical staff who served. International Women’s Day is good opportunity to remember their achievements and sacrifice.

Continue reading “Remarkable Women of the Salonika Campaign”

Ghosties and ghoulies and long legged beasties …

A Halloween offering from ‘The Mosquito’, reprinted in the Salonika Reunion Association’s final, souvenir album: Salonika Memories, 1915-1919, edited and produced by G E Willis, OBE, JP – the SRA’s long-standing Editor – and published in May 1969 …

Continue reading “Ghosties and ghoulies and long legged beasties …”

Australians and New Zealanders on the Serbian Front

My thanks go to Australian author Bojan Pajic for sharing a link with us to a fascinating article on the Australian War Memorial website about Australians and New Zealanders who served on the Serbian Front.

Continue reading “Australians and New Zealanders on the Serbian Front”

International Nurses Day

Here are some pictures for International Nurses’ Day …

Lt Vincent Drew

My thanks go to Ben Drew who, some months ago, sent us this fascinating account of his great uncle’s service in the Salonika campaign.

Away from the Western Front and the ‘Turin men’

By Keith Edmonds

Many of you will be familiar with ‘Away from the Western Front’ (AFTWF), which was a First World War centenary project funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund and was supported by the expertise of the Salonika Campaign Society. Salonika featured as a campaign in several of the AFTWF sub-projects including their work with homeless veterans and the Sandham Memorial Chapel and also Castle Drogo where one of their stonemasons, Pte WG Arscott, fought and died in Salonika with the 10th (Service) Battalion, Devonshire Regiment. Continue reading “Away from the Western Front and the ‘Turin men’”