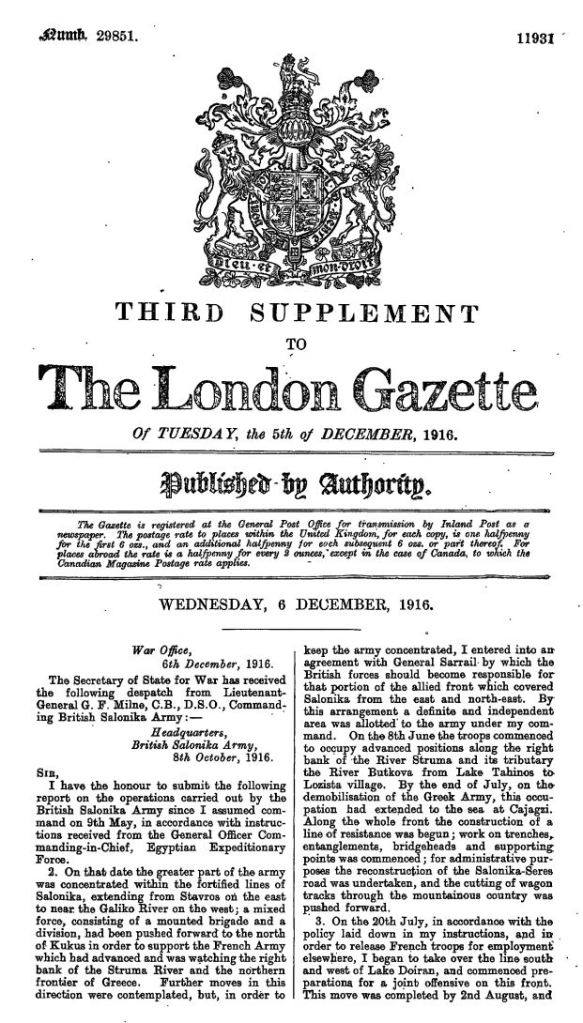

On this day, May 9th 1916, Lieutenant General George Francis Milne succeeded Lieut-General Bryan Mahon to become overall Commander-in-Chief of British Troops in Macedonia. Five months later, in October 1916, Milne submitted a report (published in The London Gazette of December 6th) summarising “the operations carried out by the British Salonika Army since I assumed command.”

To begin with, Milne states, “…in order to keep the army concentrated, I entered into an agreement with General Sarrail [French general and overall commander of the Allied forces in Salonika] by which the British forces should become responsible for that portion of the allied front which covered Salonika from the east and north-east. By this arrangement a definite and independent area was allotted to the army under my command.”

It’s interesting to read primary sources such as this against a wider background of historical perspective and analysis. In, ‘Under the Devil’s Eye’ Alan Wakefield and Simon Moody provide the context for Milne’s comments, “The new British commander was soon tested by the Frenchman’s brinkmanship when Sarrail stated that he had orders from Paris to launch an offensive and was prepared to do so with or without British assistance. Milne realised that, with his forward troops in close contact with the French, the BSF would either be dragged into an attack, which was beyond his operational remit, or, by holding back, risk accusations of failing to support an ally. He skilfully sidestepped the issue by asking for a separate British zone of operation… Sarrail agreed to the proposal and at a stroke Milne had disengaged his troops from the French.”

That analysis gives another layer of understanding to Milne’s report of how, “…in accordance with the policy laid down in my instructions, and in order to release French troops for employment elsewhere, I began to take over the line south and west of Lake Doiran…” and explains how actions in the area made it possible, “to shorten considerably the allied line between Doiran Lake and the River Vardar and on 29th August, in agreement with General Sarrail, I extended my front as far as the left bank of the river so as to set free more troops for his offensive operations.”

Politics aside, the rest of Milne’s report is a readable account of the first few months of his command in which he gives credit to the sections of his command and the men – and women – involved in the British side of the campaign.

You can download and read Milne’s entire report here. ‘Under the Devil’s Eye’ is available here.

Featured image, General Sarrail, commander of Allied forces in Macedonia (16 January 1916 – 22 December 1917), with General Sir George Milne, commander of the British Salonika Force from 9 May 1916. Source, IWM